HAVING arrived in Britain on a student visa little more than a year into her first term as prime minister, one of my earliest impressions of Margaret Thatcher was based on her performance at the Conservative Party conference in October 1980.

Here she notoriously declared: “To those waiting with bated breath for that favourite media catchphrase, the ‘U-turn’, I have only one thing to say: ‘You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning’.”

There was something in her unpleasantly smug tone of voice that made her speechwriter’s reasonably clever turn of phrase come across as an arrogant platitude.

Not long afterwards, she came across as utterly implacable in the face of hunger strikes by Irish nationalist prisoners.

Recently released cabinet documents show that, contrary to her public posture, Thatcher was open to the idea of back-channel negotiations with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), primarily because of the international attention the hunger strikers had begun to attract — particularly after their leader, Bobby Sands, had successfully contested a parliamentary by-election.

He was the first among them to die, followed by Francis Hughes. Ultimately, there were eight more. The prisoners were not demanding to be freed. They essentially wanted their political status, of which they had been stripped, to be restored. The Thatcher regime was willing, rather, to see them die. The scenario somehow did not square with my picture of a western liberal democracy.

It also substantially aided the political fortunes of Sinn Fein, the IRA’s political wing. And some years later Thatcher strayed into Kafkaesque territory when she decreed that the likes of Gerry Adams could be seen but not heard, the idea being to deny them “the oxygen of publicity”.

The farcical consequence of this was that when they appeared on television, their words had to be spoken by actors. Unlike many of the Thatcher government’s other actions, that never made the slightest bit of sense.

There was, after all, a certain logic behind the so-called economic rationalism and the widespread privatisation, the spending cuts, the vicious attacks on unions. It wasn’t by any means a pleasant logic, and its consequences — mass unemployment, increasing disparities of wealth and a deeply polarised society — were foreseeable.

But Thatcher, enraptured by the ideas of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, and impressed by the changes the ‘Chicago boys’ had wrought in Chile under her friend Augusto Pinochet’s brutal military dictatorship, was determined to change the mainstream western welfare capitalism paradigm.

The circumstances were propitious in several ways. Ronald Reagan, echoing the small-government mantra, took up residence in the White House in 1981.

The following year, Argentina under military leader Leopoldo Galtieri invaded the Falklands, a minuscule British colony in the South Atlantic, providing Thatcher with an excuse for a military expedition, and the attendant jingoism deflected attention from the domestic havoc her policies were wreaking.

A few years later, the changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union facilitated the projection of a rawer form of capitalism as the only path worth following. In retrospect, Thatcher’s statement “I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together” was not so much an endorsement as a kiss of death.

I left Britain shortly after Thatcher’s electoral landslide in 1983, and the opportunity for a return visit never arose until last year. Much had inevitable changed in the interim, but there was also a powerful sense of déjà vu, what with another Tory government implementing deep cuts in public spending and bouts of urban rioting.

David Cameron dismissed the rioters as nothing but criminals — consciously or otherwise echoing Thatcher and her ministers 30 years earlier, in the wake of eruptions in parts of London, Liverpool and Manchester.

In 1981 as in 2011, the outbursts were widely attributed to alienation, deprivation and racist policing. Back in the Thatcher era, the response was to reinforce police armouries — and the added weaponry came in handy during the government’s prolonged confrontation with miners a couple of years later.

Thatcher’s legacy has lately resurfaced in Britain as a bone of contention primarily on account of Phyllida Lloyd’s movie The Iron Lady, which has been attacked from left and right as an inaccurate portrait of the former prime minister.

However, as its maker accurately professes, the film is essentially rumination on old age; to the extent that a few of the key events from her political past are fleetingly represented on the screen, they appear as subjective flashbacks, refracted through the prism of an elderly woman’s decaying mind.

Whether an essentially apolitical feature film about Margaret Thatcher makes much sense is a different matter. Meryl Streep’s Oscar-worthy impersonation of the woman in her political prime as well as in her dotage is riveting. The notions it might plant in the minds of those who go into the cinema hall with little foreknowledge of what she meant to Britain and the world may leave much to be desired.

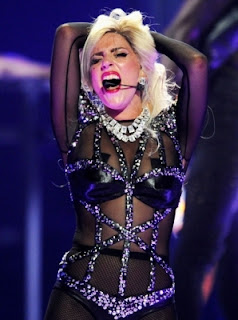

As one critic suggested, they might view her, somewhat sympathetically, less as the Iron Lady than as Lady Gaga. Another commented, accurately, that the movie depicts Thatcher without Thatcherism.

That creed was, much to his predecessor’s delight, eagerly pursued by Tony Blair. Having anointed him as her rightful heir, Thatcher was mightily miffed when the Blair government inconvenienced Pinochet by putting him under house arrest pending a court hearing on a Spanish extradition request.

It might have been interesting, artistically, to depict a conversation between the two radical right-wing has-beens at the English country mansion where the former Chilean dictator was housed.

That would, no doubt, have conformed with the senescence angle. Or perhaps Thatcher could have been shown making small talk with Nelson Mandela, whom she dismissed as a terrorist while deploring sanctions against the apartheid regime.

For a woman from a lower middle-class background to reach the Tory pinnacle and then hold power for 11 years was no doubt a noteworthy achievement. But she made an awful mess of her years at Number 10. Baroness Thatcher’s memory may now be selective — but that’s no excuse for anyone else forgetting her baleful contributions to a depressing decade.

No comments:

Post a Comment